Every fortnight we feature a seagrass meadow from around the world. This week, Marjolijn Christianen shares her experiences working in the beautiful tropical island of Derawan in Indonesia. Marjolijn is currently a PhD student at Radboud University in The Netherlands. She has a blog detailing her experiences working with turtles and seagrass.

——————————-

by Marjolijn Christianen

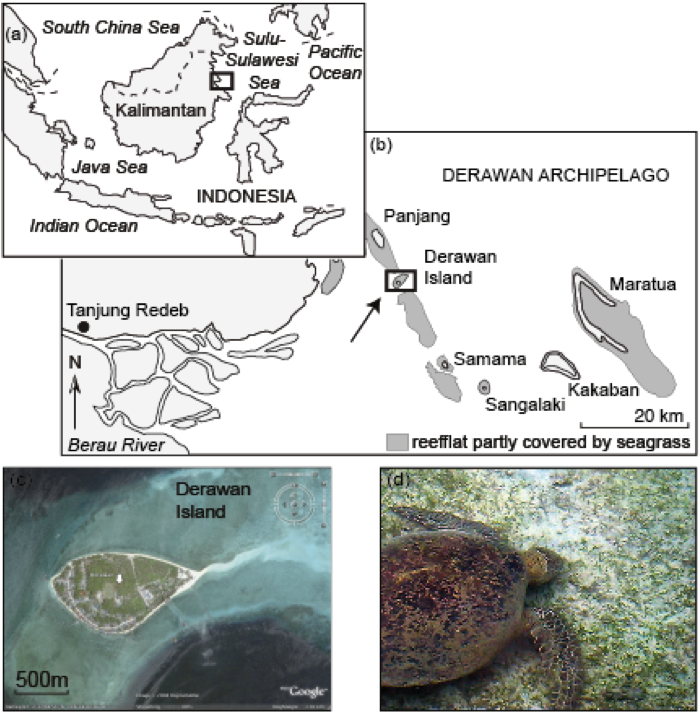

The Derawan Archipelago, is a hotspot of biodiversity and located in front of the Berau River on the mainland of East Kalimantan, Indonesia. In recent decades the once pristine rainforest and mangroves have been quickly transformed into palm oil plantations, coal mines and shrimp farms. Since all this activity is concentrated around the rivers it expected that the adjacent estuary will experience great effects of the increasing sediment and nutrient loads that will negatively affect the marine life & biodiversity of the adjacent estuary. So what is the effect of this on the seagrasses here?

(a) Map of the a Indo-Pacific Ocean with (b) The Derawan Archipelago and the (c) location of the exclosures on Derawan Island (d) Leaves are intensively grazed by green turtles, and a detritus layer is absent.

Following a pilot expedition of a Dutch group of marine biologists in 2003, we started with a 5 year PhD project in cooperation with the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) and based ourselves on the small & beautiful Island of Derawan. The island is surrounded by a large shallow area (light-blue in picture c above) which is dominated by a mono species Halodule univervis meadow. On the other islands of the archipelago you can also find other species like Cymodocea rotundata, Cymodocea serrulata, Halophyla ovalis (with very rare dugong tracks), Enhalus acoroides, Thalassia hemprichii, Syringodium isoetifolium.

We found that the effect of increasing nutrient loads proved to be much less than the effect of the local grazers. Directly after arrival I was amazed by the extremely shortly grazed leaved, that were also very thin. It just looks like there is someone mowing the underwater seagrass lawns every day. And the extremely high densities of green turtles (Chelonia mydas) were found responsible for this. In our latest paper (Christianen et al. 2011, Journal of Ecology, link http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2011.01900.x/citedby) we estimated that these hungry grazers graze 100% of the daily primairy production of the seagrass meadow.While populations of green turtle have dramatically declined at most other places, green turtle hotspots like Derawan could teach us about the historical role of the role of these megaherbivores. The green turtle not only drives structure and functioning of their foraging ground but also increases the tolerance of seagrass ecosystems to eutrophication (Christianen et al. 2011).

The majority of our fieldwork on Derawan focuses on unraveling the interactions between seagrasses, turtle grazing and increasing nutrient loads. A fancy fieldwork station is lacking but this stimulates to interact a lot with the (families of the) local fisherman that have a lot of knowledge about the ecosystems.

On a small island with 1500 people we always have enough attention from the local kids (left). Daily fieldwork life, working on exclosures 400 meters offshore of the island (right)

Working on such a remote island is amazing because you are surrounded by marine life such as green turtles, mantas, dolphins, frog fish, and (my favorite) the robust ghost pipefish (looks like a Thalassia leaf). But on the other hand you also have to plan your experiment well and buy your materials a full day travelling away, or even further. And don’t step in a stingray like I did because this will definitely slow down your fieldwork.