This is a the first of a series of fortnightly articles featuring seagrass meadows around the world. This week, Dorothée Pête of the University of Liege takes us to Calvi Bay in Corsica, which is one of her research field sites.

———————–

By Dorothée Péte

Although it’s nearest water body is the river Meuse, the University of Liege in Belgium has always had a strong interest in marine sciences. To strengthen the link between Liege and the sea, a research station was built in the late sixties, in Calvi Bay in Corsica, France. This research station with a catchy acronym – STARESO which stands for STAtion de REcherches Sous-marines et Océanographiques – which in English means “Station for underwater and oceanographic research” is a base for marine research carried out by the University.

Map of Calvi Bay (taken from Google Earth) showing the locations of STARESO, Punta Oscellucia, sewage outfall area, zone where Caluerpa racemosa was identified and location of fish farms. and other seagrass sites in the locality.

Calvi Bay is a wonderful place for studying seagrasses in the Mediterranean. It has two species of seagrasses, Posidonia oceanica (which is endemic to the Mediterranean Sea) and Cymodocea nodosa. This bay is of particular interest because all the major threats present in the Mediterranean Sea can be found in such a small area – making it a natural choice for studying impacts via field experiments. Plus, the view is spectacular both above and below water so you can easily understand why our lab (Laboratory of Oceanology) is working there and why I wanted to write a note to explain our field work.

Calvi Bay, Corsica - the view above water

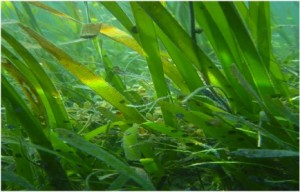

Let’s begin with the STARESO. In front of the research station, you can find a continuous meadow of P. oceanica. This seagrass canbe found from near the surface (5 m depth in STARESO) to about 40 m depth, so scuba diving is essential if you want to work in this meadow. The meadow at the STARESO site is a reference one, thanks to its good state of health. Our lab has been following it for years, with a particular focus on the seagrass itself (its growth, density and leaf litter accumulations), but also on its epiphytes, nutrients and trace elements contents, food webs and on organisms living in the sediment. Of course, environmental parameters such as nutrients in surrounding and pore waters and temperature are monitored as well. The meadow is also part of the SeagrassNet monitoring program. In situ experiments like shading, microcosms, sediment loading and nutrients and trace elements dynamics (e.g. inside isolated jars) are being carried out there too.

Studies being carried out in Calvi Bay (from L-R): Nutrient dynamics, microcosm experiments and shading experiments

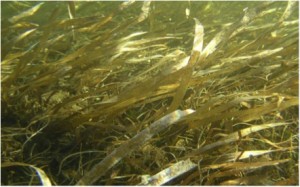

Just next to STARESO, near Punta Oscellucia, large amount of underwater leaf litter accumulations are present and are exported onto the surrounding beaches and there are currently studies focused on the dynamics of those litter patches and organisms living inside them.

Seagrass wrack accumulations off Punta Oscellucia

Sadly, it’s not all about beautiful seagrass and crystal clear waters in Calvi Bay as there are quite a number of threats in the area. It is widely known that the Mediterranean Sea is a major tourist attraction and a hub for marine recreation. In summer, tourists from all over the world invade the city of Calvi, causing direct stress to the seagrasses there through activities such as yachting but also indirectly due to increased sewage, which is another important (although slightly less glamorous) topic that our lab is studying by looking at the zones of the seagrass meadow situated near the sewege outfalls from Calvi.

Fish farming activities have been increasing in the Mediterranean Sea, and Calvi Bay has a small aquaculture industry. It is situated above a P. oceanica bed but it is fortunately quite well managed, so the impact on the meadow is very small. However, we are also studying the P. oceanica ecosystem in that zone for a better understanding of fish farming impacts.

Fish Farms floating in the waters off Calvi Bay.

The last (but not least!) threat that was identified very recently in Calvi Bay is the presence of an invasive seaweed species Caulerpa racemosa. We are just beginning to work on that subject and for now, it looks like it shouldn’t be a problem for P. oceanica in that zone. However, in other parts of the Mediterranean Sea, invasive seaweeds are causing more and more troubles to seagrass meadows. They are taking over areas formerly colonized by large beds of seagrasses and seem more resistant to environmental impacts than the seagrasses. In that way, they are becoming a threat for the coastal biodiversity of the Mediterranean by causing modifications in the habitats of numerous organisms (some of which are commercially important species) and a switch in communities, leading to a decrease in biodiversity.

I hope that I have convinced you how lucky we are to have such a nice site for field work, but if you want to see more and learn more about STARESO and the awesome people in my lab working seagrasses, please visit our website and check out the links below:

Laboratory of Oceanography, University of Liege:

http://www2.ulg.ac.be/oceanbio/Page%20acceuil_ENG.html

STARESO:

http://www.stareso.ulg.ac.be/Stareso/Stareso.html

http://www.stareso.com/

A new manual aimed at building knowledge and raising awareness of seagrass habitats has hit the shelves (well not literally)! The training manual, titled “Seagrass Syllabus” was developed by The World Seagrass Association and Seagrass-Watch in partnership with Conservation International.

A new manual aimed at building knowledge and raising awareness of seagrass habitats has hit the shelves (well not literally)! The training manual, titled “Seagrass Syllabus” was developed by The World Seagrass Association and Seagrass-Watch in partnership with Conservation International.