Website for ISBW10 is up! click here

22nd May is International Day for Biodiversity and the theme for 2012 is Marine Biodiversity. In celebration, we will be featuring a series of articles on seagrass. This week, Michael Durako writes about his experiences visiting North Queensland, Australia.

———————————————————-

Photos and text by Michael J. Durako

During the Fall 2011 semester while on research reassignment from my University, I spent 5 weeks with the Marine Ecology Group (MEG), Fisheries Queensland in Cairns hosted by Dr. Robert Coles, Dr. Michael Rasheed and my former student Katie Chartrand. During this research visit I focused on assessing changes in leaf spectral reflectance as an indication of seagrass physiological condition, specifically in response to light and desiccation stress. During my visit I was able to sample two relatively pristine sites on Green Island, which is 24 km offshore of Cairns, and several highly-impacted sites in Gladstone Harbour, which is 250 km north of Brisbane. Before departing for Cairns I was able to assemble a field compatible spectral reflectance system to obtain spectral reflectance measurements in situ using, with the help of Randy Turner and Lance Horn at the University of North Carolina Wilmington Center for Marine Science. The system consisted of a 25m long optical fiber reflectance probe connected through a variable neutral density filter to an Ocean Optics spectrometer with data acquisition controlled by OOI Spectra Suite software via a waterproof external switch and a Panasonic Toughbook PC.

Figure 1. Ocean Optics reflectance setup at Green Island.

Figure 1. Ocean Optics reflectance setup at Green Island.

After calibration and testing the reflectance measurement system at the Northern Fisheries Center in Cairns, I set up a short-term shading experiment on Green Island. Shades, which reduced irradiance by 70%, were placed over Halophila ovalis (Hov) and Thalassia hemprichii (Th) located along the inner fringe of a seagrass bed on the south side of the island. The spectral reflectance of leaves of these two species were compared between adjacent full-sun and shaded plots from 0800 to 1400h to determine if this bio-optical characteristic exhibited short-term diurnal changes in high and low light treatments. The resulting reflectance spectra showed significant species, time and treatment differences.

Figure 2. Shade plots over Halophila ovalis and Thalassia hemprichii at Green Island.

Figure 2. Shade plots over Halophila ovalis and Thalassia hemprichii at Green Island.

During my visit, I was very fortunate to be able to participate in an aerial (helicopter) seagrass survey trip to Mourilyan Harbor, 80 km south of Cairns. Because of the high tidal range (4 m), turbid water and presence of saltwater crocodiles, aerial survey techniques are broadly used by MEG in their seagrass assessment work in northern Queensland. This aerial approach may be applicable and more efficient for some of our FHAP sampling sites in Florida Bay. We were able to sample 126 sites in about 2 hours and never got our feet wet!

Figure 3. Hovering (altitude 1m) at a seagrass sampling site in Mourilyan Harbor. Helen Taylor of MEG is entering the GPS location of the sampling station on an ARC GIS map using a touchscreen PC. Carissa Fairweather is communicating sampling information to the pilot. My job was to enter the seagrass data on the field datasheets.

Figure 3. Hovering (altitude 1m) at a seagrass sampling site in Mourilyan Harbor. Helen Taylor of MEG is entering the GPS location of the sampling station on an ARC GIS map using a touchscreen PC. Carissa Fairweather is communicating sampling information to the pilot. My job was to enter the seagrass data on the field datasheets.

I visited Gladstone Harbor over Sept 27-29th as part of a compliance sampling trip for Queensland Fisheries. During this trip I compared the spectral reflectance of submerged versus exposed seagrasses at four sampling sites: Pelican North, Whiggins, Fisherman’s Island and Pelican South. Because of the large tidal range (3-4m) and high turbidity, we could only sample during the afternoon low tides. Reflectance data indicated distinct spectra between submerged and exposed leaves for both Zostera capricorni and Halophila ovalis at all four sites (see example spectra in Fig. 6; note separation of spectra from 500-680nm).

Figure 4. Launching the Fisheries Queensland R/V Halophila at Gladstone Harbor.

Figure 4. Launching the Fisheries Queensland R/V Halophila at Gladstone Harbor.

Figure 5. Sampling exposed Zostera capricorni at Pelican South, Gladstone Harbor.

Figure 5. Sampling exposed Zostera capricorni at Pelican South, Gladstone Harbor.

Figure 6. Normalized reflectance of submerged (wet) versus exposed (Dry) Zostera capricorni at North Pelican, Gladstone Harbor.

Figure 6. Normalized reflectance of submerged (wet) versus exposed (Dry) Zostera capricorni at North Pelican, Gladstone Harbor.

Near the end of my visit, I was able to visit Green Island again. My plan was to repeat the shading study in another location on the Island. However, because of an early occurrence of Irukandji jellyfish, which are extremely venomous, the island was closed to swimming, within an hour of my arrival on the island. One of the resort divers was stung on the lip (she had on a stinger suit) and had to be MediVaced off the island by helicopter. Thus, I had to limit my sampling to only low tide. To make lemonade from lemons, I revised my sampling to be similar to what I had done in Gladstone Harbor. I compared the spectral reflectance of submerged and exposed Thalassia hemprichii and Halophila ovalis. The reflectance spectra were again distinct between species and between submersed and emersed shoots, although the differences were more subtle than those at Gladstone. The results from this short field visit suggest that spectral reflectance provides a rapid assessment method that is sensitive to changes in seagrass physiological condition and it provides another tool in our arsenal of non-invasive physiological ecoindicators.

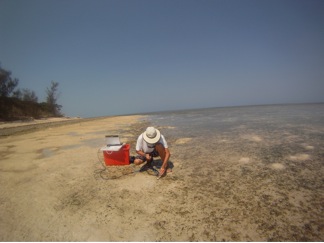

Figure 7. Measuring spectral reflectance of exposed Halophila ovalis at Green Island.

Figure 7. Measuring spectral reflectance of exposed Halophila ovalis at Green Island.

Posted in Notes from the field | Tagged Australia, Notes from the Field | Comments Off on Notes from the field: Reflections from down under

This year’s theme for International Day for Biodiversity is Marine Biodiversity. The WSA blog will be featuring a series of articles on seagrass this month so watch this space!

Visit the Convention on Biological Diversity page here.

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on International Day for Biodiversity, 22nd May 2012

Every fortnight we feature a seagrass meadow from around the world. This week, Elizabeth ‘Z’ Lacey writes about Akumal Bay, an ecosystem in the Caribbean off the coast of Mexico. Z is finishing her Ph.D. at Florida International University in Miami, Florida.

—————————————

Photos and text by Z Lacey

I have a confession. I did not go to Akumal Bay to study the seagrass beds; I went to study the coral reefs. Before you kick me off the World Seagrass Association blog, hear me out. I first came to Akumal Bay, Quintana Roo, Mexico to study the return of an important herbivore to the coral reef community BUT I was quickly and irreversibly intrigued by the seagrass beds and the graceful green sea turtles in short order. Does that redeem me in your eyes, fellow seagrass lovers?

But I get ahead of myself. Let me introduce you to a beautiful place that I’ve been working in for the past four years. Akumal Bay is located along the MesoAmerican Reef on the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico and its name means ‘place of the turtles’ in Mayan. It is a unique environment as it’s one of the few public access beaches for locals as well as serves the surrounding tourist populations coming from Playa del Carmen, Tulum and Cancun. There are lots of interested stakeholders, which is a challenge for the managers of this important ecosystem. Incredibly this bay is monitored by the non-governmental organization Centro Ecologico Akumal (www.ceakumal.org) and Director Paul Sanchez-Navarro. They rely heavily on donations and volunteer stewards to monitor the coral reefs, water quality and abundant turtle population. To do this they hold turtle walks, give informative lectures in the education center, run a recycling program, provide life jackets/snorkeling vests and many other initiatives, all free of charge to visitors and the residents of the nearby pueblos.

Unlike Siti’s last post on the diversity of species to be found in South Sulawesi, the seagrass meadows in Akumal typically consist of just three seagrasses: Thalassia testudinum, Syringodium filiforme and sparse Halodule wrightii intermixed with calcareous green macroalgae. The seagrass beds are patchy throughout the lagoon from the shoreline to the reef approximately 250 meters offshore. In some areas of the bay, patch reefs are interspersed throughout the seagrass meadow, providing refuge for fish, urchins and other diverse marine life.

Akumal Bay is easily accessible by tourists groups from land as well as those entering on boats via the channel through the adjacent barrier reef. Part of my research is considering this impact by humans on the seagrass beds and how the herbivores, both sea turtles and fish, have shaped this ecosystem. Similar to other regions along the Mayan Riviera, this area is experiencing dramatic population growth and even further tourism development. While the fate of these seagrass beds is unknown, change is inevitable. CEA is in a difficult position as they try to protect the ecosystem with their limited financial resources while also listening to the needs of the local residents, tour operators and businesses, which rely on the bay mainly for tourism income rather than as a food source.

Volunteers come from all around the world for a three month adventure at CEA and learn skills such as coral reef identification and sea turtle tracking. Throughout the years I’ve had volunteers from France, Netherlands, Germany, the Philippines and of course Mexico as they assist in my research along with their other volunteer duties. For some, such as my new friend Yvonne Kleinschmidt pictured here, they were completely unaware of the different types of seagrass before I took them into the field to make them honorary seagrass rangers. It’s been fun for me to teach workshops on identifying seagrass and macroalgae to the volunteers as part of their reef monitoring training.

Before you think it’s all work and no play in Akumal, I have to mention the many Mayan ruins to explore, cenotes to swim in and cities like Playa del Carmen to visit! Not to mention the amazing local cuisine and fresh fruits and veggies available at the farmer’s market in the town square. A day off from the field is rich in cultural experiences as well as ecological discovery – another reason I’ve come back to Akumal year after year. And while I initially studied the coral reefs, you can see how the interesting marine life living within the seagrass beds and the stories waiting to be explored were able to pull me into Akumal Bay!

Posted in Notes from the field | 6 Comments »

Every fortnight we feature a seagrass meadow from around the world. This week, I thought I’d take a stab at writing about a recent trip I made to a seagrass meadow on a sand cay called Barang Lompo in South Sulawesi.

By Siti M. Yaakub (text) & Marjolijn Christianen (photos)

The Spermonde Archipelago is the stuff of seagrass legends. I say this because I’ve heard it talked about A LOT. The area has had a long succession of seagrass researchers (mostly Dutch) conducting their studies in the area. So when I got to tag along with Marjolijn (Mayo) and her two masters students Peter and Iris to visit some seagrasses off Makassar in South Sulawesi, I was pretty darn excited. We set off early from the hotel and after haggling for a boat, we set off for Barang Lompo, which is a coral island just north west of the town of Ujung Pandang in Makassar. In just under an hour (which is pretty impressive for our tiny vessel) we were there.

You know that feeling you get when you come across a seagrass meadow you haven’t been to before? You’re peering into the water, and you’re met with a carpet of awesome green, your heart leaps and you get tingles down your spine in anticipation of what you might find, and all you wanna do is jump right in and swim around like a crazed person checking off the number of species of seagrass you can find? That’s pretty much what happened.

The meadow didn’t disappoint, we spent a very happy hour or so exploring, ID-ing seagrass and checking out the cool critters going about their daily business.

The meadow was predominantly Enhalus acoroides, Halodule uninervis and Thalassia hemprichii with lots of Halophila ovalis in between.

After an hour or so of swimming, we were getting hungry, so we got back onto the boat and headed to a nearby island called Bono Batang to grab some lunch. Mayo was hoping to catch a glimpse of some turtles, but the tide was pretty low so chances of finding grazing turtles in the seagrass is pretty low.

When we got to the island, there was some excitement at the jetty. A couple of local boys had spotted a very large puffer fish in the seagrass surrounding the jetty and were taking turns diving in after it.

After lunch, we took a short stroll to a shop near the jetty, which turned out to be a souvenir shop – selling stuff collected from the sea. We had a quick chat with the owner and Mayo asked him about the occurrence of green turtles in the area, turns out there haven’t been green turtle sightings in decades! Lots of Hawksbills but no Greens 🙁

Mayo having a chat with the shop owner. Above her hands the skeleton of a dugong and hanging on the pillar to her right is a preserved turtle that's for sale to tourists.

When asked about the turtles he has for sale, the owner said that they are no longer allowed to catch turtles in the waters around the area and that the existing stock he has in his shop are all from before the new law was passed. We also learned that turtle meat is sometimes used as filler in local dishes because it’s cheaper than beef.

As we walked back to the jetty, we came across a rather disturbing sight. Marine rubbish was strewn everywhere along the shore. Turns out that there isn’t a proper waste disposal system on the island and it all goes into the sea. A sobering note to leave on, given that these islands are very densely populated. As we left you can actually see the impact marine litter is having on the seagrass beds just adjacent to the island. Will this be the fate of Barang Lompo as well?

————————————————————–

If you think that the SE Asian seagrass beds are over-represented on this blog, you’re absolutely right. I mean they’re awesome and all, but we are sorely lacking contributions from our North and South American, Mediterranean, African and Australian counterparts. I have to rely on YOU for these because much as I’d like to go around and snorkel/swim/dive/walk in all the seagrass beds in the world, I have supervisors to answer to and like most PhD students, a lack of funds. So please help me keep this blog alive and going! Send me your articles! The rest of the world, REPRESENT!! Love, Siti 🙂

Posted in Notes from the field | 1 Comment »